The Greek Christian author Basil of Caesarea (c.330–379) is usually remembered by church historians of late antiquity as an extremely important theologian, whose defense of the deity of the Holy Spirit in the final stages of the Arian controversy played a critical role in the formulation of the orthodox Christian teaching

Read moreSpecial Pre-Conference: Martyrdom in the Early Church

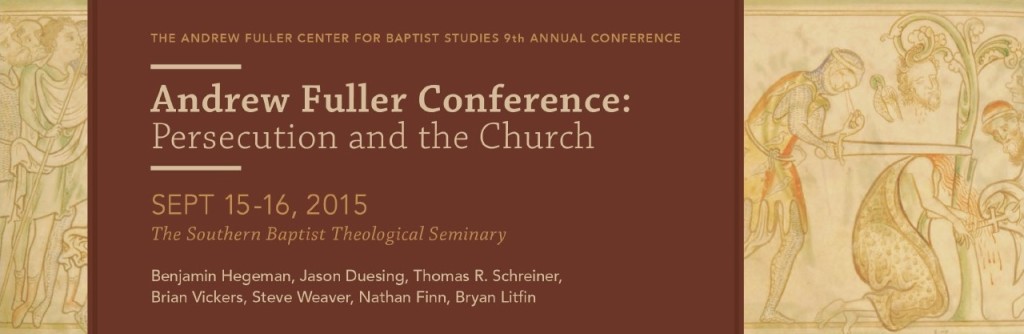

Join us Monday, 14 September 2015, in Louisville, KY for a pre-conference co-sponsored with the Center for Ancient Christian Studies on “Martyrdom in the Early Church: Reality and Fiction.” The event is free to all students, faculty, and friends.

This event will precede our annual two-day conference that will be held on September 15-16, 2015 on the campus of The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary. To learn more and to register for the conference, click here.

“In order that we too might be imitators of him”: The Death of Polycarp and the Imitation of Jesus

By Shawn J. Wilhite and Coleman M. Ford

The Martyrdom of Polycarp offers an eyewitness account to the death and martyrdom of Polycarp from the church at Smyrna to the church at Philomelium (Mart.Pol. Pref.). As the narrative unfolds, some of the motifs that emerge relate to imitation. That is, the narrative of Polycarp’s death evoke the reader to imitate the death of Polycarp (Mart.Pol. 1:2).

This AD 2nd century event details three different martyrdom accounts. It praises the nobility of Germanicus, who fought with wild beasts and encouraged the “God-fearing race of Christians” through his death (Mart.Pol. 3:1–2). It discourages the concept of voluntary martyrdom as Quintus “turned coward” when he saw the wild beasts. Such voluntary pursuit of martyrdom does not evoke praise from fellow sisters and brothers because the “gospel does not teach this” (Mart.Pol. 4).

However, the narrative details the “blessed Polycarp” and his noble death (Mart.Pol. 1:1). These events are aimed to demonstrate how the “Lord might show us once again a martyrdom that is in accord with the Gospel” (Mart.Pol. 1:1). So, the narrative models for the reader a martyrdom that is worthy of imitation as it is patterned after “the Gospel.”

The Martyrdom account portrays Polycarp as a model of Christ’s life. For example, Polycarp waited to be passively betrayed (Mart.Pol. 1:2). The night before Polycarp’s betrayal, he is praying with a few close companions (Mart.Pol. 5:1). He prays “may your will be done” prior to his arrest (Mart.Pol. 7:1; cf. Matt 26:42). Furthermore, Polycarp is betrayed on a Friday (Mart.Pol. 7:1) and seated on a donkey to ride into town (Mart.Pol. 8:1)—similar to the “triumphal entry” and garden of Gethsemane events. On the verge of death, Polycarp offers up a final call to the Father (Mart.Pol. 14:3). While Polycarp is tied to the stake, an executioner is commanded to come stab Polycarp with a dagger (Mart.Pol. 16:1). Even the execution offers a similar to the confession of the centurion’s statement “Certainly this man was innocent!” (Mart.Pol. 16:2; Luke 23:47).

Not only do Polycarp and the surrounding events reflect a similar Gospel tradition, the villains in Polycarp’s story are re-cast in light of the passion villains. Polycarp is betrayed by someone close to him (Mart.Pol. 6:1). The captain of the police is called “Herod” (Mart.Pol. 6:2; 8:2; 17:2). The author(s) of the Martyrdom make sure to slow the narrative so that the reader makes the necessary connection to the Gospel accounts by saying, “who just happened to have the same name—Herod, as he was called” (Mart.Pol. 6:2). Moreover, those who betrayed Polycarp ought to “receive the same punishment as Judas” (Mart.Pol. 6:2). There is an army to capture Polycarp, similar to the Gethsemane scene (Mart.Pol. 7:1). The band of captors recognizes the piety of Polycarp in a similar way the group of soldiers bowed before arresting Him (Mart.Pol. 7:2; cf. John 18:6).

The Martyrdom narrative mimics the Gospel passion narratives. Whether it focuses on the personal character traits of Polycarp, the narrative of Polycarp’s journey to death, the secondary, seemingly accidental themes, or even the story’s villains, the Martyrdom of Polycarp is reshaped around gospel tradition.

As the narrative of the death of Polycarp unfolds, Polycarp’s character mimics the Lord so “that we too might be imitators of him” (Mart.Pol. 1:2). The blessed and noble characters of martyrdom are modeled after the narrative of Jesus tradition so as to invite readers to imitate Polycarp as he is imitating the Lord Jesus (Mart.Pol. 19:1).

Those in the early church saw patterns to imitate in the life of Jesus in regards to how to conduct oneself in the wake of impending martyrdom. Today, many Christians are faced with how to imitate those patterns as well. Both in America where persecution comes in word and thought, and in places like Syria where martyrdom is a real and present danger, reading Polycarp and other early Christian martyr stories empowers believers to follow the ultimate pattern which is Christ.

---------------------------------------

Join us on September 15-16, 2015 on the campus of The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary for this conference on Persecution and the Church in order to learn from examples from church history and around the globe that will encourage believers today to face persecution.

Join us on September 15-16, 2015 on the campus of The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary for this conference on Persecution and the Church in order to learn from examples from church history and around the globe that will encourage believers today to face persecution.

Reading Plan for the Latin Fathers (April-June 2014)

By Michael A.G. Haykin

April 19–26 Read Tertullian’s Against Praxeas Question: What are Tertullian’s main arguments against modalism and how does he anticipate the later Trinitarian formula “three persons in one being”?

April 27–30 Read Cyprian, To Donatus Question: Outline Cyprian’s understanding of conversion.

May 1–7 Read Cyprian, On the Unity of the Catholic Church Question: What are the marks of the true church according to Cyprian and how does he substantiate his view?

May 8–15 Read Novatian, On the Trinity Question: How does Novatian show from Scripture that Jesus is God?

May 16–23 Read Hilary of Poitiers, On the Trinity, Book 1 Question: Outline Hilary’s conversion.

May 24–31 Read Augustine, Confessions (the whole book) Question: Outline the way that Augustine depicts God as The Beautiful.

June 1–7 Read Augustine, City of God 1.1–36; 4.1–4; 11.1–4; 12.4–9; 13.1–24; 14.1–28; 15.1–2; 20.1–30; 21.1–2; 22.8–9; 22.29–30 Question: What is Augustine’s understanding of history?

June 8–15 Read Patrick, Confession Question: What is Patrick’s understanding of the missionary call?

Download the Reading Plan for the Latin Fathers (PDF)

_______________

Michael A.G. Haykin is the director of the Andrew Fuller Center for Baptist Studies. He also serves as Professor of Church History and Biblical Spirituality at Southern Baptist Theological Seminary. Dr. Haykin and his wife Alison have two grown children, Victoria and Nigel.

The Fathers—my mentors

By Michael A.G. Haykin

Do the Fathers lead logically to the full-blown theology of the Roman Catholic Church or Eastern Orthodoxy? Not at all: Epiphanius of Salamis condemned the use of icons and pictures; Cyprian described Stephen, the bishop of Rome, as the Antichrist; Augustine’s view of the presence of Christ is much closer to Luther than Trent; and on and on. Read Calvin’s Institutes and see how often he cites the Fathers, esp. Augustine. And why? Because he believed they supported him, not the Roman Church. And he was right. Thomas Cranmer, the theological and liturgical architect of Anglicanism, was one of the leading patristic scholars of his day. No, the Fathers are not necessarily the root of the Roman Catholic Church or Eastern Orthodoxy. They are just as much my Fathers as they are theirs—and I, a full-blown unrepentant Evangelical—am not ashamed to own them as my theological mentors and forebears. This does not mean I believe everything they believed, even as I do not believe everything my great hero Andrew Fuller believed (his view that John Wesley was a crypto-Jesuit is plain ridiculous, e.g.).

If you wish to see how contemporary Evangelicals read the Fathers, check out the series of books beginning to be published this year by Christian Focus and of which I am the series editor: “Early Church Fathers.”

____________________ Michael A.G. Haykin is the director of the Andrew Fuller Center for Baptist Studies. He also serves as Professor of Church History and Biblical Spirituality at Southern Baptist Theological Seminary. Dr. Haykin and his wife Alison have two grown children, Victoria and Nigel.

“The nights are wholesome”: Shakespeare on Christmas

By Michael A.G. Haykin

Melito of Sardis and possibly Eusebius of Caesarea in the early Church believed that when Christ was born all wars ceased during his lifetime. This small text from William Shakespeare’s Hamlet is a variant of that:

Some say that ever ’gainst that season comes Wherein our Saviour’s birth is celebrated, The bird of dawning singeth all night long: And then, they say, no spirit dares stir abroad; The nights are wholesome; then no planets strike, No fairy takes, nor witch hath power to charm, So hallow’d and so gracious is the time.

(Hamlet, Act 1, Scene 1, lines 157–163)

Not affirming I believe this—but it does tell you something about the great Bard’s beliefs. At some point I should share the great debt I owe Shakespeare.

____________________ Michael A.G. Haykin is the director of the Andrew Fuller Center for Baptist Studies. He also serves as Professor of Church History and Biblical Spirituality at Southern Baptist Theological Seminary. Dr. Haykin and his wife Alison have two grown children, Victoria and Nigel.

Dr. Haykin contributes to New Book on the Atonement

By Steve Weaver

Releasing this month from Crossway is a massive new book on the doctrine of definite atonement titled From Heaven He Came and Sought Her: Definite Atonement in Historical, Biblical, Theological, and Pastoral Perspective. As the title suggests, this volume will approach the doctrine historically, biblically, theologically, and pastorally.

Edited by David and Jonathan Gibson, the volume assembles a world-class group of scholars to address their "particular" topics. Dr. Haykin drew from his patristic training to write his chapter: “We Trust in the Saving Blood”: Definite Atonement in the Ancient Church.

There is a website dedicated to promoting the book. On the website, you will find a list of the contributors, the table of contents, endorsements, and a free preview (PDF) of the book.

The book is slated to release on November 30, 2013, but is already available for pre-order from Amazon.com.

________________

Steve Weaver serves as a research assistant to the director of the Andrew Fuller Center for Baptist Studies and a fellow of the Center. He also serves as senior pastor of Farmdale Baptist Church in Frankfort, KY. Steve and his wife Gretta have six children between the ages of 2 and 14.

Prayer: Common Ground for Origen of Alexandria and Fuller of Kettering

By Dustin W. Benge

Throughout church history men have written treatises on the subject of prayer using the Lord’s Prayer (Matt 6:9–13) as a framework to shape their pastoral instruction. Perhaps no connection could be made between early church father, Origen of Alexandria (184/185–253/254) and Andrew Fuller (1754–1815), except they both gave insightful expositions on the Lord’s Prayer.

Origen’s treatise on prayer (De Oratione) reads more as a practical pastoral handbook than a major theological treatise. Origen gave a beautiful interpretation of the opening address of the Lord’s Prayer, “Our Father, who art in heaven.” Origen believed a Christian could not proceed with the following petitions and requests contained within the Lord’s Prayer until this opening phrase is rightly understood. Origen pointed out that the Old Testament does not know the name “Father” as an alternative for God, in the Christian sense of a steady and changeless adoption.[1] Only those who have received the spirit of adoption can recite the prayer rightly. Therefore, the entire life of a believer should consist in lifting up prayers that contain, “Our Father who art in heaven,” because the conduct of every believer should be heavenly, not worldly. Origen explained:

Let us not suppose that the Scriptures teach us to say “Our Father” at any appointed time of prayer. Rather, if we understand the earlier discussion of praying “constantly” (1 Thess 5:17), let our whole life be a constant prayer in which we say “Our Father in heaven” and let us keep our commonwealth (Phil 3:20) not in any way on earth, but in every way in heaven, the throne of God, because the kingdom of God is established in all those who bear the image of Man from heaven (1 Cor 15:49) and have thus become heavenly.[2]

Like Origen, Fuller began his exegesis of the Lord’s Prayer by establishing that prayer must be dependent upon the character of the one to whom we are allowed to draw near, namely, “Our Father.” The recognition of God as “Our Father” implies that sinners have become “adopted alien[s] put among the children.”[3] Those adopted into God’s family can therefore rightly approach God as their Father but it must, as Fuller clarifies, be through a Mediator. Fully consistent with the Messianic age, Christ set himself within the context of the prayer as the One through which the Christian must come if he or she is to approach God as “Father.” Fuller states, “The encouragement contained in this tender appellation is inexpressible. The love, the care, the pity, which it comprehends, and the filial confidence which it inspires, must, if we are not wanting to ourselves, render prayer as a most blessed exercise.”[4]

Origen and Fuller arrive at the same conclusion. They both see the phrase, “Our Father,” as the affirmation within the Lord’s Prayer that anchors the proceeding requests and brings great confidence within the one praying. Understanding God as “our Father” is the gift that causes the joy of prayer to be realized.

[1] On Prayer (De Oratione) (Coptic Orthodox Church Network).

[2] Origen, “On Prayer,” 125.

[3] The Complete Works of Andrew Fuller, 1:578.

[4] The Complete Works of Andrew Fuller, 1:578.

________________________

Ellen Charry and Implications for Historiography

By Ryan Patrick Hoselton

Ellen Charry’s work, By The Renewing of Your Minds: The Pastoral Function of Christian Doctrine (1997), is among those rare gems that challenge you to consider a serious paradigm shift in the way you do theology. Even more, I think her arguments have implications for historiography.

Charry contends for the restoration of theology that is sapiential (which she understands as knowledge that emotionally engages the knower to the known), aretegenic, and salutary. She attempts to show that the best Patristic, Medieval, and Reformation theologians thought, wrote, and spoke about God in this way. Theologians such as Basil of Caesarea, Anselm of Canterbury, and John Calvin insisted on correct doctrine—on knowing God accurately—because it was conducive to moral transformation and flourishing in the Christian life. Knowing and loving God rightly enables authentic imitation of him, and this is the key to human virtue, excellence, and happiness. Thus, pastoral concern drove their theological reflection and engagement in doctrinal controversy.

Charry contends for the restoration of theology that is sapiential (which she understands as knowledge that emotionally engages the knower to the known), aretegenic, and salutary. She attempts to show that the best Patristic, Medieval, and Reformation theologians thought, wrote, and spoke about God in this way. Theologians such as Basil of Caesarea, Anselm of Canterbury, and John Calvin insisted on correct doctrine—on knowing God accurately—because it was conducive to moral transformation and flourishing in the Christian life. Knowing and loving God rightly enables authentic imitation of him, and this is the key to human virtue, excellence, and happiness. Thus, pastoral concern drove their theological reflection and engagement in doctrinal controversy.

The modernism of Locke, Hume, and Kant severed faith and sapience from reason, eliminating both from the category of knowledge. Charry suggests that these epistemic shifts facilitated the waning of sapience from theology. Modern academic theology, preoccupied with pursuing knowledge of God on the terms of this modern epistemology, reduced theological reflection to factual knowledge, scientias. However, for classical theologians like Augustine, the goal of scientias was to move the knower to sapientia, wisdom.Knowing factual things about God must be paired with knowing God in wisdom and love. The verity of a doctrine rests largely in its result. For example, Basil of Caesarea argued that the Holy Spirit must be God on the basis that he makes us more like God and unites us to him—only God can do that. Basil contended for this doctrine because he believed that if his congregants denied it they would not grow in godliness. These classical theologians did not separate scientias and sapientia in the way that the modern Academy often does. For them, theology and pastoral theology were synonymous. Their doctrinal battles and treatises functioned primarily to protect and promote their congregants’ holiness.

Charry’s thesis applies to church historians as well. Treatments in historical theology that are limited to broad sweeps of ideologies could fall into the modern trap of severing scientias from sapientia. Historians must avoid imposing this modernist separation on past theological thought. Church historians are responsible for uncovering the pastoral concerns that lie behind the subject’s theological reflection. As Robert Darnton says, the point is “to show not merely what people thought but how they thought—how they construed the world, invested it with meaning, and infused it with emotion” (Darnton, 1985, 3). The historian must investigate the relationship between a theologian’s ideas and his behavior, shepherding, and spirituality. This kind of historiography will assist theologians and pastors in understanding why historic Christian doctrines mattered and still matter to the lives of believers.

__________________

Ryan Patrick Hoselton is pursuing a ThM at The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary. He lives in Louisville, KY with his wife Jaclyn, and they are expecting their first child in August.

Ryan Patrick Hoselton is pursuing a ThM at The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary. He lives in Louisville, KY with his wife Jaclyn, and they are expecting their first child in August.

New Book by Michael Haykin: Tri-Unity: An Essay on the Biblical Doctrine of God

Tri-Unity: An Essay on the Biblical Doctrine of God

Tri-Unity: An Essay on the Biblical Doctrine of God

From the Publisher:

Early Christian contemplation on the Trinity is one of the most fascinating intellectual and spiritual conversations in the history of western thought.

In this new work by Dr. Michael A.G. Haykin on this bedrock doctrine of the Christian Faith, follow some of the greatest figures in the Ancient Church — men like the missionary theologian Ireanaeus of Lyons, the African bishop Athanasius and the monastic reformer Basil of Caesarea — as they study the Bible, grapple with how to talk about the Triune God and determine what exactly this means for the Christian life.

Their thinking is just as relevant now as it was when they first put pen to papyrus.

“What a rich story this is, and one the reader will understand and appreciate much better because of Haykin’s masterful work.” — Bruce A. Ware, The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary, Louisville, KY

“Michael Haykin’s, with his impeccable scholarship, has produced a short, readable account that will help many to appreciate these struggles and to grow in their knowledge of God. Buy it, read it, give it to a friend.” — Robert Letham, Director of Research, Senior Tutor in Systematic and Historical Theology, Wales Evangelical School of Theology

“In a clear and learned way, Michael Haykin connects the Bible to Athanasius and the Cappadocian Fathers…” — Carl R. Trueman, Westminster Theological Seminary, Philadelphia, PA

Product Details

Format: Paperback Language: English Publisher: NiceneCouncil.com Year: 2012 Pages: 75 ISBN: 098825480-8

Posted by Steve Weaver, Research Assistant to the Director of the Andrew Fuller Center for Baptist Studies, Dr. Michael A.G. Haykin.

More on centres of love

In the latest round of debate regarding the so-called “new atheism,” Christian theologian Doug Wilson takes on Christopher Hitchens in a published give-and-take on the topic Is Christianity Good for the World?[1] Hitchens is convinced that Christianity, along with religion in general, poisons everything good in life. And thus, for him, the answer to the question in the book’s title is a resounding no. Hitchens’ answer, however, is one that would have amazed numerous pagans living in the Roman Imperium in the first four centuries after Christ. The love, generosity, and showing of mercy of believers to those outside of the Christian community was, according to Henry Chadwick--that great patrologist who died this past summer and on whom I still need to write a small appreciation--“probably the most potent single cause of Christian success” during the period of the Roman Imperium.[2]

[1] Is Christianity Good for the World? (Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, 2008).

[2] Henry Chadwick, The Early Church (Rev. ed.; London: Penguin Books Ltd., 1993), 56.

Justin Martyr on the value of the truth

The citation from Philip Doddridge that was quoted in an earlier post on this blog is an echo--albeit probably unconscious--of this from the second-century Christian apologist Justin Martyr: “the lover of truth must choose, in every way possible, to do and say what is right, even when threatened with death, rather than save his own life.” [1]

[1] First Apology 2.1.

Where to Start in Reading Patristics

I was asked by one reader (www.letmypeopleread.blogspot.com ) about where I would recommend beginning a reading programme in the Fathers. Here is my brief reply. (And thanks, brother, for the great question). I would start with Robert Louis Wilken, The Spirit of Early Christian Thought: Seeking the Face of God (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2003). Then: Christopher A. Hall, Reading Scripture with the Church Fathers (Downers Grove, Illinois: InterVarsity Press, 1998). Finally, a third book that is a gem, but not easy is Jaroslav Pelikan, The Christian Tradition. A History of the Development of Doctrine. Vol. 1: The Emergence of the Catholic Tradition (100-600) (Chicago/London: University of Chicago Press, 1971).

And do not forget getting into the Fathers directly. Start with Augustine, Confessions, trans. R.S. Pine-Coffin (Harmondsworth, Middlesex: Penguin, 1961) [this is the translation I like, but there are others]. Or read through an excellent collection by Steven A. McKinion, ed., Life and Practice in the Early Church. A Documentary Reader (New York/London: New York University Press, 2001). Another favourite of mine is Basil of Ceasarea, On the Holy Spirit, trans. David Anderson (Crestwood, New York: St. Vladimirs Press, 1980).

For a good overview of the period, see the relevant pages in Tim Dowley ed., Introduction to the History of Christianity (1990 Rev. ed.; repr. Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 1995) and for the key leaders, see John D. Woodbridge, ed., Great Leaders of the Christian Church (Chicago: Moody Press, 1988). The latter is regrettably out of print, but second-hand copies can be gotten easily. I have also had published Defence of the Truth: Contending for the truth yesterday and today (Darlington, Co. Durham: Evangelical Press, 2004), which deals with theological challenges faced by the Ancient Church.

I did blog on this back in 2006: see WHAT TO READ OF THE FATHERS?

Why Seek out the Fathers

A dear friend, John Clubine, recently passed along to me a couple of pages from The Berean Call, 23, No.3 (March 2008), an article by T.A. McMahon entitled “Ancient-Future Heresies.” There are a number of things in the article with which I would wholeheartedly agree. But at one point the following is stated: “…it takes very little scrutiny of men like Origen, Ireaeus, Tertullian, Clement of Alexandria, Cyprian, Justin Martyr, Athanasius, John Chrysostom, Cyril of Jerusalem, Augustine, and others, to see their flaws, let alone their heresies. For example, Origen taught that God would save everyone and that Mary was a perpetual virgin; Irenaeus believed that the bread and wine became the body and blood of Jesus when consecrated, as did John Chrysostom and Cyril of Jerusalem; Athanasius taught salvation through baptism; Tertullian became a supporter of the Montanist heresies, and a promoter of a New Testament clergy class, as did his disciple Cyprian; Augustine was the principal architect of Catholic dogma that included his support of purgatory, baptismal regeneration, and infant baptism, mortal and venial sins, prayers to the dead, penance for sins, absolution from a priest, the sinlessness of Mary, the Apocrypha as Scripture, etc. It’s not that these men got everything wrong; some on certain doctrines, upheld Scripture against the developing unbiblical dogmas of the roman Catholic Church. Nevertheless, overall they are a heretical minefield. So why seek them out?” (p.4).

John Lukacs, a marvelous historian, has recently said that one of the reasons why we need to do history is that there is so much bad history out there. And this paragraph is a case in point! Much of what is said here is out and out erroneous, some of it needs nuancing and parts of it are right. It would take a book to respond adequately, and a blog is probably not the best place in engage in developing an adequate response.

But suffice it to say this: the paragraph ends with a very erroneous statement and a very important question. The deeply erroneous statement: “overall they are a heretical minefield.” Wow! There have been some in the past who argued thus, but they were usually ones who disagreed with the Reformation impulse and felt that the entire history of the church between the Apocalypse of John and the Reformation was an utter wasteland. Best to forget it all and start anew.

This was not the view of the Reformers, who felt that the Fathers of the Church could aid them in the Reformation needed in their day. Not that the Reformers believed everything that the Fathers wrote. They tested all against Holy Scripture. But they did believe that the Fathers more often supported them than they did their Roman Catholic opponents.

The question: “why seek them out?” Because the Reformers like Calvin and Cranmer and Knox believed that the Fathers were important witnesses to biblical truth and they bore witness to the grace of God at work in the Church.

Book Review of Fik Meijer, the Gladiators

Fik Meijer, The Gladiators: History’s Most Deadly Sport, trans. Liz Waters (New York: Thomas Dunne Books, 2007), xviii+267 pages. I must admit that the gaudy cover of this book was off-putting at first glance. I picked it up at a variety store in an airport terminal and frankly, I thought it looked somewhat hokey. A quick perusal of the book, though, soon convinced me otherwise. And as I read it over the next few days I realized that this 2003 work by Dutch historian Fik Meijer is a gem. The very fact that the topic of gladiators is of perennial interest provides space for Meijer to argue that the modern West is as deeply fascinated by violence as Rome ever was.[1]

He first explains how the bloodiest “sport” in history evolved to become a key aspect of Roman society. Details regarding the lives of the gladiators—everything from the various types of gladiators who fought in the arena to the financial details of the shows—and the building of the Colosseum in Rome (the most spectacular of over 200 such amphitheatres in the Roman world by the third century a.d.) are then given in a lively prose style that is at once informative and fascinating reading.

The chapter “A Day at the Colosseum” brilliantly recreates what it would have been like to have attended one of the shows for a day of bloody and brutal entertainment. Although I have read the accounts of Christian martyrs for a good number of years now, I was completely unaware that their deaths would have taken place during what Meijer terms the lunchtime interval between the morning programme when there would have been animal fights and the afternoon “attraction” of the main gladiatorial fights (p.147-159). Meijer actually draws on the North African theologian Tertullian (fl.190-220) for some of his information, citing the second-century author more than half a dozen times.

Three final chapters deal with sea battles, the burials of slain gladiators and the end of the gladiatorial shows. Although Constantine issued legislation abolishing the shows in 325 a.d., it was not until the fourth decade of the following century that the shows finally ended.

All in all this is an excellent work and helps students of the Ancient Church understand in part why that ecclesial tradition, reacting against the violence of their world, was so solidly committed to non-violence.

[1] See pages 1-12, and his brief reviews of the movies Spartacus (1960) and Gladiator (2000) (p.220-231) as proof.

Clement of Alexandria and the Term “Father”

The use of the term “father” for Christian mentors is quite ancient. Here is a quote from Clement of Alexandria that indicates this: “Words are the progeny of the soul. Hence we call those that instructed us fathers” (Stromateis 1.1.2-2.1).

Of course, Paul uses it thus in 1 Thessalonians 2:11. Our Lord emphasizes, though, that the term cannot be used in such a way that it compromises the fact that God the Father alone is our true Father. Any other father in Christ is relative compared to Him (Matthew 23:9).